Part 2: Renewable Energy Enters the Limelight in Upcoming Presidential Campaign

A continuation of the Guardian’s article “Is Hillary Clinton’s ambitious solar energy goal for the US workable?”. We pick up again in the article with the second goal in the plan.

Speaking to reporters on Monday, Clinton noted that further federal investment would be needed to incentivise the sector’s push to 33%. In a fact sheet, the campaign flagged the resuscitation of tax credits and some innovation and regulatory incentives.

“That [the return of tax credits] is hardly a sure thing, given that at least one chamber of Congress will inevitably be Republican controlled during at least the first two years of any new president’s term,” said Zindler.

People in the US may care less about climate change than they do about cost

Jürgen Weiss, Brattle Group consultancy Jürgen Weiss, head of climate change at the Brattle Group consultancy, said incentives were important as the industry remained relatively tiny, with low public awareness. A large percentage of costs for installers of residential solar are wrapped up in selling the technology to a sceptical public who have relatively low electricity costs and little concern for climate change. “The big part is convincing people to sign up in the first place. People in the US may care less about climate change than they do about cost,” he said.

Although the technology, regulatory and labour costs are roughly similar, the price of installing residential solar in Germany (where high electricity costs, strong public acceptance and large government incentives have driven a huge push to solar) is around $1.50 (£1) per watt cheaper than in the US. Even if half of Clinton’s target of 140GW of solar by 2021 were to come from residential (as opposed to utility) solar panels, that equates to a cost difference of more than $100bn, mostly spent on advertising and sales.

John Reilly, an energy economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said the targets would be a challenge “in terms of providing incentives to build that much”.

Weiss said: “I do think those costs will come down as the market matures and people get more informed.” The danger, he said, was providing too much tax-payer funded incentive early on. In Germany and the UK, the solar industry has come under political pressure for being too successful when subsidies were high and now suffers from accusations of being a ‘subsidy junky’.

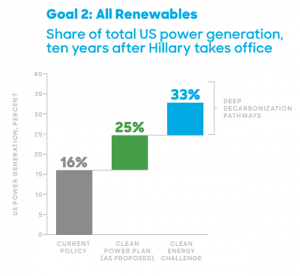

It’s important to clear up some ambiguity in the Clinton rhetoric. From her renewables campaign video, “a 10-year goal of generating enough renewable energy to power every single home in America” does not mean every home is going to have its own clean energy supply. The residential sector uses roughly a third of the total electricity generated. So a 33% renewable goal means the country will be generating this much clean energy, but not all of it will end up in homes.

But factories and office buildings don’t vote and the promise, as my colleague Suzanne Goldenberg points out, allows Clinton to sound like she’s liberating bill payers from utilities. It is also clear that Clinton’s focus on solar (as opposed to wind) is aimed at the voting bill payer. Solar even garners support among some Republicans because of the freedom it offers from regulation and bills.

The Department of Energy has found that wind energy can affordably reach 20% of electricity generation by 2030. And, under Obama’s Clean Power Plan, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts it will be the biggest contributor of new renewable capacity throughout the 2020s.

As part of her announcement, Clinton pledged to uphold the Obama administration’s heavily-opposed restrictions on the carbon emissions of power stations, which are expected to accelerate the already rapid shut-down of coal plants across the country. This capacity will mostly be taken up by cheap gas, but there will be space for renewables if they can compete.